This is a div block with a Webflow interaction that will be triggered when the heading is in the view.

Intro

For years, different security researchers and media outlets have surfaced isolated fragments of Indonesia’s gambling cybercrime ecosystem, but no one has seen its true scale. Malanta’s research now reveals the more holistic picture: a long-running operation active since at least 2011 that aligns with the resources, persistence, and operational maturity typically associated with a state-sponsored threat actor. What began as small gambling activity has evolved into a multi-layered infrastructure spanning hundreds of thousands of gambling domains, thousands of malicious Android applications, extensive domain and subdomain hijacking, and stealth infrastructure embedded inside enterprise and government websites worldwide. Blending illegal gambling, SEO manipulation, malware distribution, and highly persistent takeover techniques, this campaign represents one of the largest and most complex Indonesian-speaking well funded, state-sponsored-level ecosystems observed to date.

Canonical Key Findings

- A hidden infrastructure that has been active for over 14 years, indicating a well-funded, organized APAC-based advanced persistent threat with sustained resources.

- The threat actor maintains 328,039 domains including 90,125 hacked domains, 1,481 hacked sub-domains and 236,433 purchased domains.

- This hacked subdomain operation spans enterprises and government entities, with evidence of TLS-terminating reverse proxies on hijacked government FQDNs used to conceal C2 traffic and facilitate cookie theft.

- Systematic exploitation of WordPress, PHP components, dangling DNS, and expired cloud assets to hijack and weaponize trusted domains.

- A large-scale Android malware ecosystem hosted on AWS S3 buckets, distributing thousands of APK droppers with C2, staging, and data-theft capabilities.

- Over 51,000 stolen credentials found in dark web forums were tied to this infrastructure, originating from gambling sites, infected Android devices, and hijacked sub-domains.

- 38 burner GitHub accounts used to host malicious templates, webshells, verification strings, and distribution artifacts.

- 480 domain lookalikes masquerading as popular organizations such as Slack, Amazon, Facebook, Instagram, Shopify and many others.

- The infrastructure shows signs of automation and AI-assisted content generation, supporting its scale and persistence.

The Indonesian Gambling Cybercrime Infrastructure

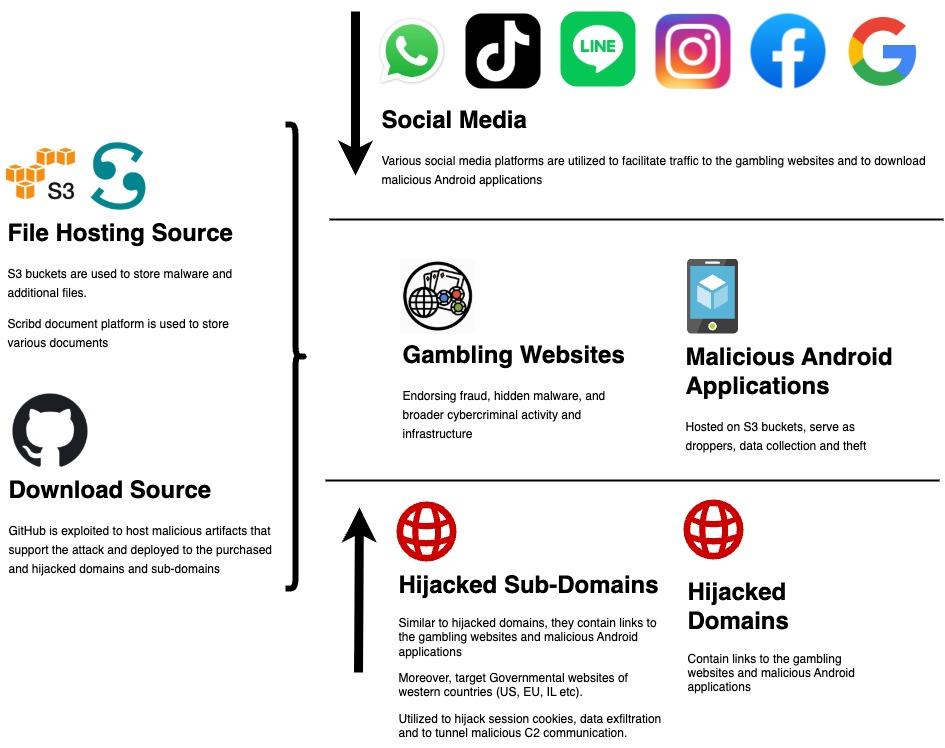

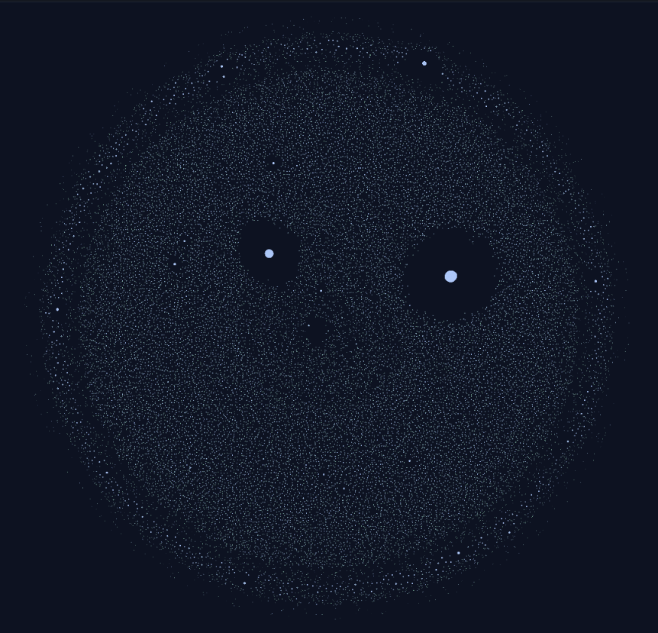

Malanta’s research team uncovered a massive infrastructure operated for the past 14 years by a sophisticated Advanced Persistent Threat (APT) that is deeply involved in the Indonesian cybercrime domain while actively exploiting governmental virtual assets worldwide. Below is a schematic visualization of its operation.

Based on our research, the APT’s operation can be divided into four main categories, as described below:

- Building, operating, and maintaining a massive cyber infrastructure to facilitate cybercrime in Indonesia, including dedicated gambling websites and malicious Android mobile malware.

- Advertising the operation described above across many social media platforms to generate traffic and increase its revenues and victims.

- Building, operating, and maintaining a large-scale infrastructure that searches for vulnerable and misconfigured WordPress domains, PHP components, dangling DNS, and expired resources to successfully exploit and hijack domains or subdomains.

- As a subset of the hijacked subdomains operation, maintaining stealth infrastructure inside Western government domains with capabilities to steal session cookies and tunnel traffic.

Below you can see a screenshot taken from Malanta’s platform, illustrating the APT’s infrastructure. The nodes consist of domain names, IP addresses, certificate data, and email addresses. The colored edges represent a connection between:

- Domain name and IP address (colored green).

- Domain name and certificate data (colored purple).

Gambling Sites Dedicated Infrastructure

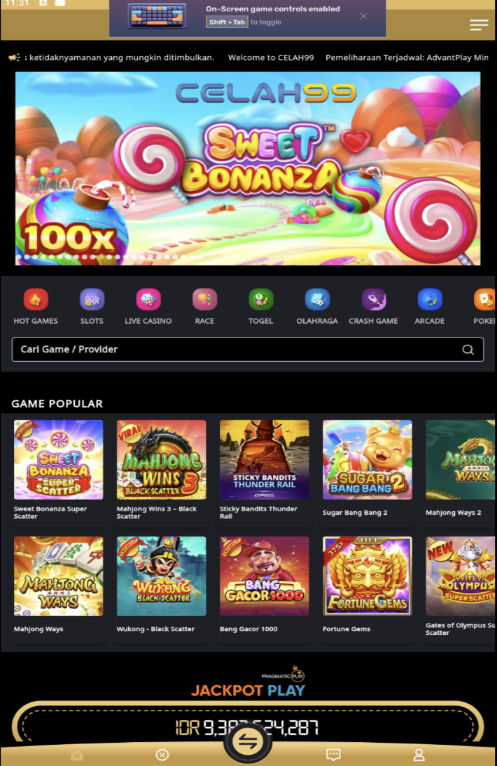

It appears that the main goal of this infrastructure is to lead users to an Indonesian-speaking gambling website. In Indonesia, all forms of gambling are illegal and pose significant cybersecurity risks, including frequent fraud, data theft, hidden malware, and links to broader criminal infrastructure.

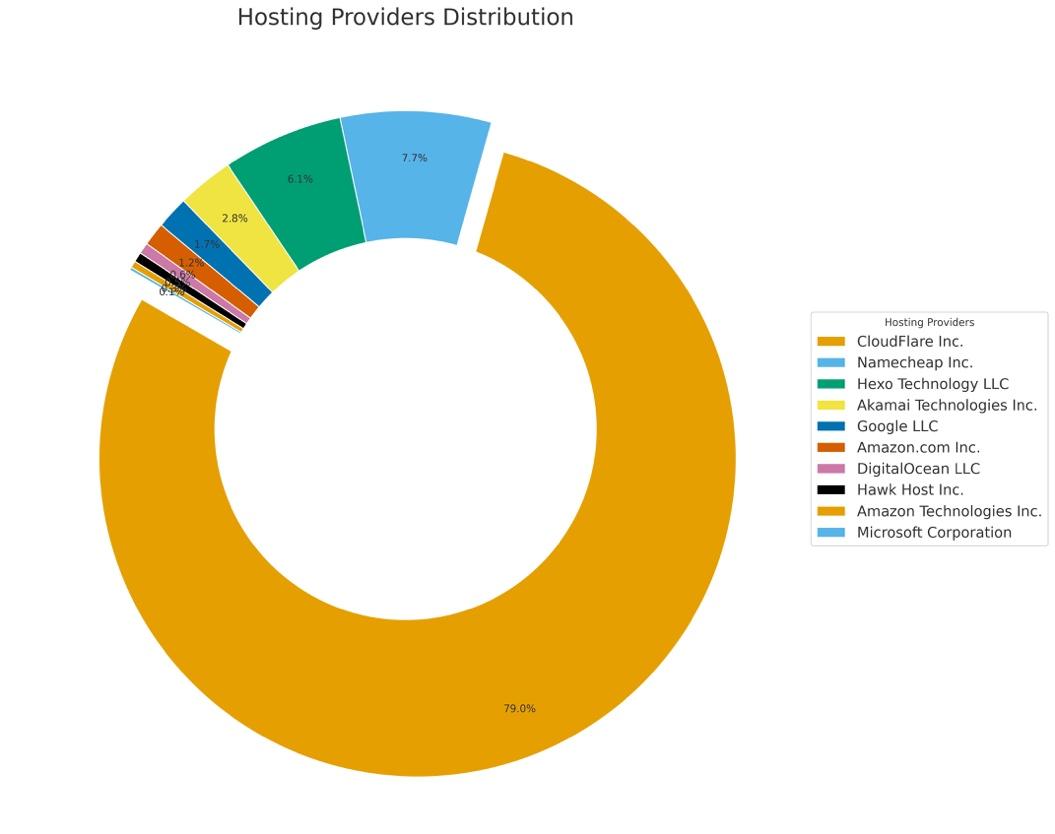

Our research uncovered 236,433 domains owned by the APT that host gambling sites. These domains are mainly hosted on Cloudflare

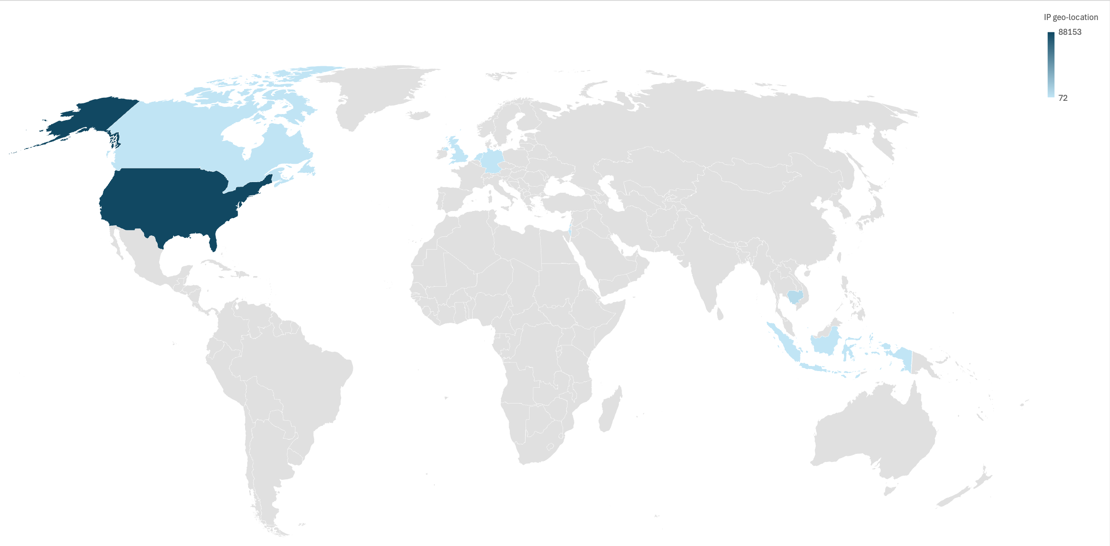

In addition, the IP addresses are mainly affiliated with U.S. geolocation. It is unclear whether this choice was made by the APT to better facilitate cybercrime in Indonesia, or whether, in a time of need, this infrastructure could be used to target additional victims in the U.S. or Europe. In that case, a predominantly U.S. based infrastructure could serve this purpose more effectively.

These domains are geolocation-sensitive, as in some cases they only allow access to the website from IP addresses in specific countries, for instance Indonesia. Below you can see our failed attempt to access the website from an IP address with Mexican geolocation, as opposed to a successful attempt from an IP address with Indonesian geolocation.

To use the site, users are required to register. During registration, the user must provide a phone number with the ‘+62’ country code (Indonesia) and details of Indonesian banks or digital payment services (such as BCA, Mandiri, BNI, BRI, CIMB Niaga, and e-wallets like DANA, OVO, Gopay, and LinkAja).

These domains are built with the same website template and utilize “livechatinc.com” for customer support.

We developed several algorithms to analyze the dataset and extract meaningful insights, each designed to provide different layers of threat intelligence value. One of these focuses on detecting domain lookalikes and typosquatting activity. By scanning the discovered domains, we identified 480 domain lookalikes.

Inspection of sample WHOIS records indicates that this activity dates back to early 2020, with the associated domains being renewed annually, demonstrating persistence and intentional operation. For example, examining slackd[.]com alongside related permutations such as slacka[.]com, slackb[.]com, and others reveals that most variants are owned by Slack or by DomainSafe (possibly Slack’s protective proxy). This suggests that the adversarial infrastructure is deliberately registering broader Slack-adjacent lookalikes, likely as part of a social-engineering or possibly a future plan to weaponize these domains for credential-harvesting to lure unsuspecting users.

Malicious Android Apps

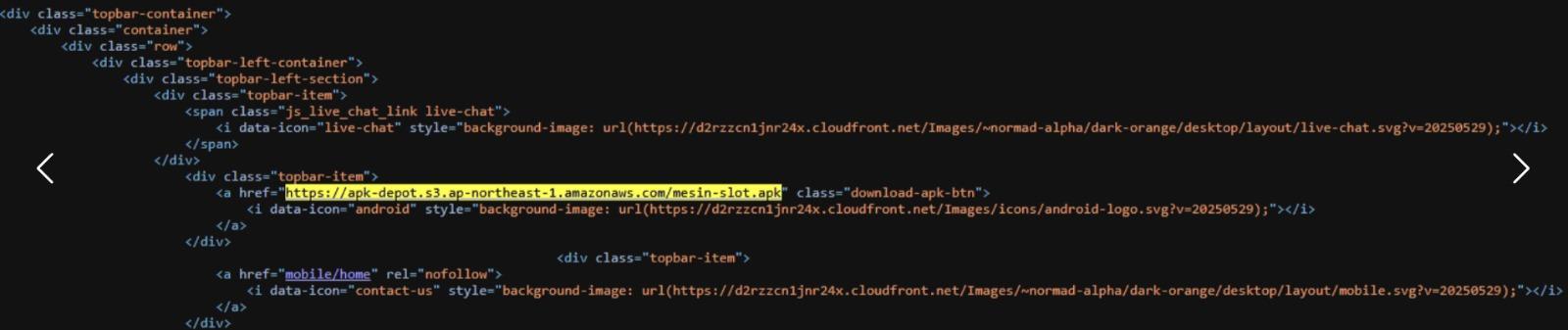

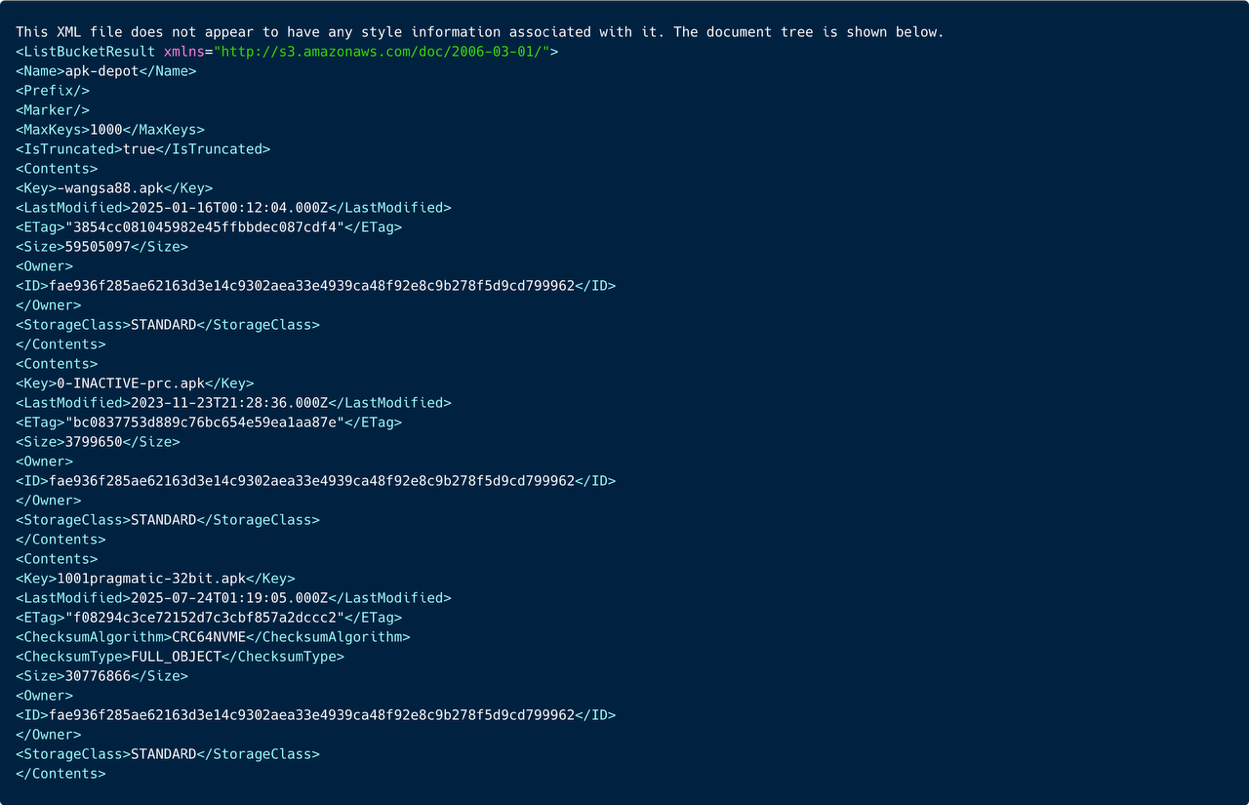

We discovered 7,700 domains that contain links to at least 20 AWS S3 buckets, of which 5 buckets were publicly available. Below you can see an exemplary website and the link in the code snippet.

The buckets are fairly active, with the last activity logged on October 18th, 2025. Further analysis of their content revealed thousands of APK files (e.g., deltaslot88.apk, jayaplay168.apk, 1poker-32bit.apk), all bearing gambling-related names.

In addition, some of the publicly available buckets also contained various inaccessible log folders, indicating activity as early as 2021.

In our lab, we analyzed a representative sample of APK files both statically and dynamically. We also used a proxy to channel the traffic, after overcoming the APT’s defense-evasion mechanisms. We observed the following malicious behaviors and capabilities:

- Upon installation, the applications downloaded additional APK files and requested their installation (INSTALL_PACKAGES + downloader components). Hence, the initial APKs downloaded by users serve as droppers/updaters for further malware.

- We saw evidence of read/write access to external storage. Thus, the malware is capable of exfiltrating data and performing payload staging.

- The app includes Google’s Firebase Cloud Messaging (FCM) push-notification features. In a normal app, FCM is used for alerts, updates, or messages. Nevertheless, the APT can misuse it to remotely send instructions or links to the infected device, allowing them to control the app without direct communication.

- Many APK files contained hardcoded credentials and API keys, which can be used for telemetry or management.

These APK files also share at least one domain (jp-api.namesvr[.]dev) that appears in network traffic from multiple samples and likely serves as a C2 server. The exposed buckets and the observed app behaviors enable large-scale distribution of fake gambling applications and the potential persistent compromise of victim devices.

Hijacked Domains and Sub-Domains

Domain and subdomain hijacking has become an increasingly common attack vector, frequently exploited by threat actors because it allows them to abuse trusted infrastructure with minimal effort.

Below some description in detail how these domains and subdomains can be hijacked:

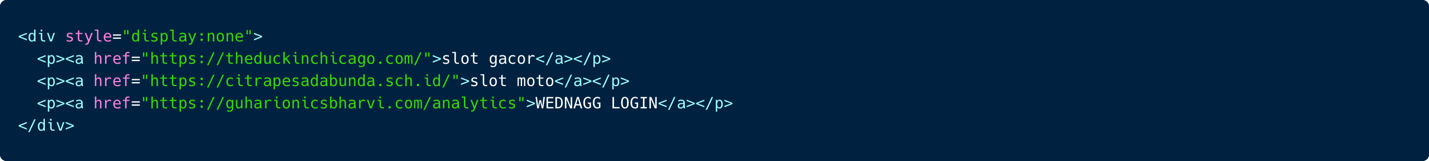

- As described in this great recent blog by Ben Martin, attackers gain initial access to WordPress sites (via vulnerabilities or misconfigurations) and hijack existing pages (such as an “About” page) by creating a new directory with the same name and placing a spam-filled index.html inside it.

- As described in an Imperva blog post, attackers scan for and exploit PHP-based web applications, looking for existing webshells or vulnerabilities. Once they find a webshell, they install a backdoor called GSocket, giving them persistent remote access to the server. From there, they deploy gambling web content and redirect site traffic to the gambling operations.

- In addition, we also saw evidence of exploitation of dangling DNS and expired resources as part of the subdomain takeovers.

Hijacked Domains

We discovered that the threat actor has hijacked 90,125 domains to upload links that redirect to gambling sites.

Threat actors target domains and subdomains for several reasons. The primary motivation is to avoid paying for a large infrastructure to host links to their gambling ecosystem. In addition, abusing a wide variety of enterprise and small business domains from different sectors and geolocations can strengthen their domain reputation and SEO ranking.

In one example, we found a hijacked personal website belonging to a doctor in Ecuador containing dozens of links to gambling domains.

Our analysis shows that the attackers are trying to conceal the gambling content inside harvested HTML content from top popular websites.

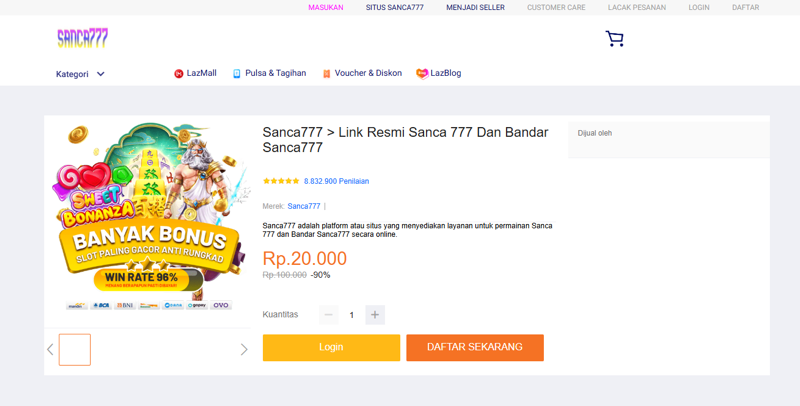

As shown above, in half of the cases the domains had a specific template based on a large company such as eBay, Lazada, etc. We found that 108,000 domains had no specific template. Our analysis shows that these 108,000 domains are hosted only on ~600 IP addresses. Thus, each IP address hosts hundreds of domains, with 92% of the IP addresses hosting at least two domains. This evidence strengthens the assumption that a single threat actor is behind this subset of domains and the entire infrastructure.

Hijacked Sub-Domains

We discovered that the threat actor has hijacked at least 1,481 subdomains. Most of them were hosted on AWS, Azure, and GitHub.

When analyzing the victims, we observed domains owned by both individuals and organizations. The victim organizations come from a wide range of sectors, including manufacturing, transport, healthcare, government, and education. Most organizations are located in the U.S., but there are also victims in Europe and Southeast Asia, as well as a significant number in Indonesia.

We identified two types of attack scenarios. The first is similar to the domain hijack vector: the threat actor hijacks the subdomain and inserts a web page that is a lookalike of popular websites such as Lazada, eBay, or Envato, as described below.

The second (and very troubling) scenario involves a focus on Western government domains. These hijacked subdomains are repurposed to capture the session cookie of the main domain. In addition, the attacker runs NGINX-based reverse proxies that terminate TLS on legitimate Fully Qualified Domain Names (FQDNs), then tunnel C2 traffic to their backend. This means the threat actor uses the government’s domain names and valid HTTPS to disguise their outbound traffic. The reverse proxy decrypts the incoming connection and then secretly forwards commands to the attacker’s C2 servers.

In plain terms, this infrastructure can serve many purposes. For instance, highly stealthy cybercrime, as traffic appears legitimate coming from a government domain, or tunneling malware C2 communication through what looks like government infrastructure.

In some of the cases we analyzed, we observed that the hijacked subdomain inherited and used the session cookie of the main domain. For example, the hijacked subdomain of a U.S. based global corporation with annual revenues of over 16 billion USD had the same cookie as the main domain.

This configuration security flaw was found in many hijacked subdomains and can easily lead to the theft of session cookies. In websites that require login information for financial services or other sensitive data, a stolen cookie can allow the attackers to gain full access to that data.

Malware and Artifacts Download Infrastructure

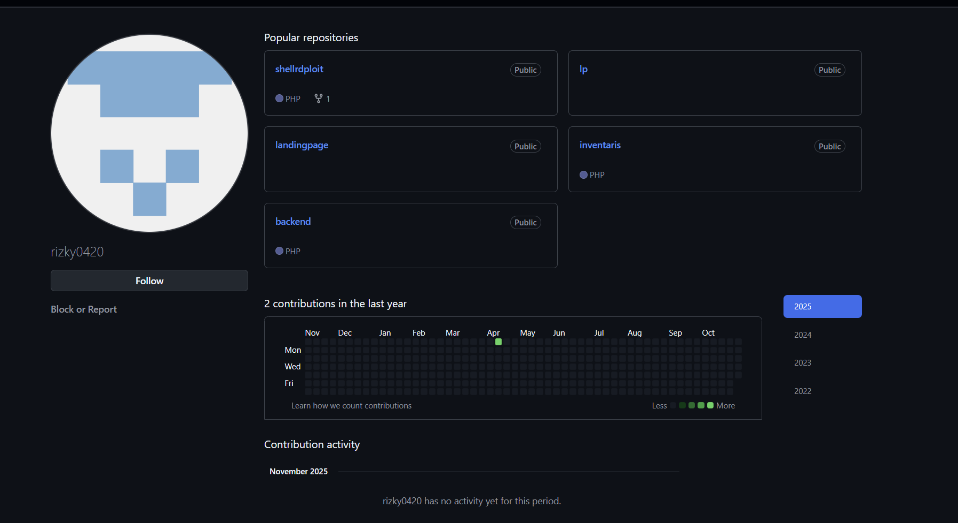

Our research led us to what we believe is part of the APT’s download and malware dissemination infrastructure. Namely, the APT is hosting malicious content in 38 burner GitHub accounts. Based on the GitHub activity charts of these accounts, we estimate that this infrastructure was created between 2022 and 2023.

Below you can see a screenshot of one of these accounts, containing the HTML files that are later uploaded to hijacked domains and subdomains.

We also saw evidence for exploit kits in some of the repositories. Below you can see a heavily obfuscated malicious PHP web shell that serves as a backdoor. It is quite heavy (1.2Mb).

We also see evidence of some of the hijacked CNAME records.

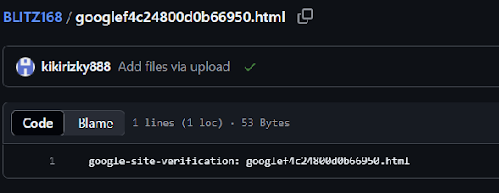

These repositories also contain Google verification strings, which is often used by Google Search Engine to validate a website, making the APT’s website more likely to appear in search results, thus attracting more potential users to the websites:

Additionally, many accounts associated with the activity seem to embed different types of web shells and malicious APK files, likely used to inject unsuspecting users with malicious content.

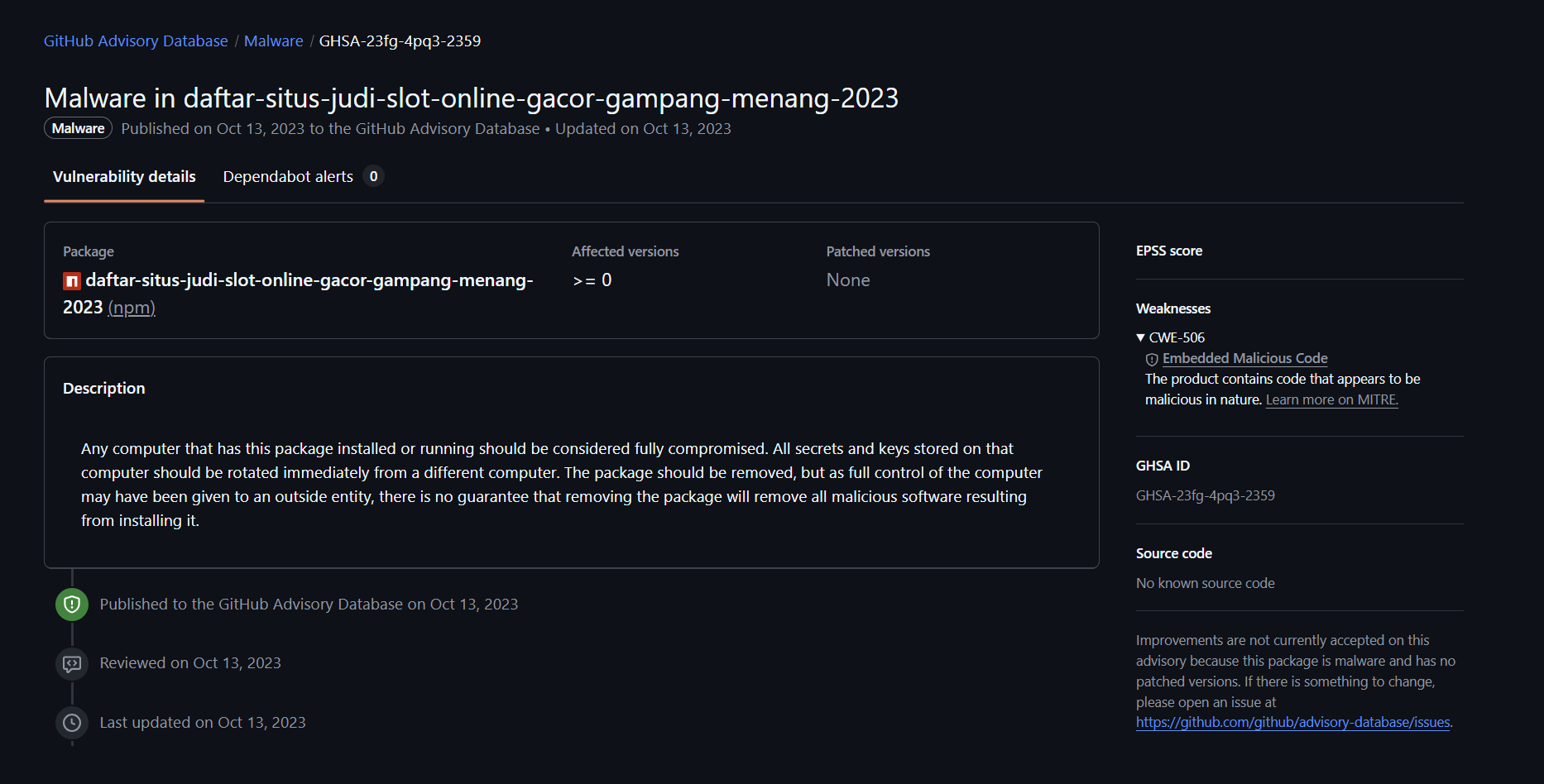

Furthermore, we’ve also detected several malicious libraries associated with the campaign, possibly fetched from associated apps and are vulnerable to remote code execution.

We assess that these accounts are used as part of the actor’s operation, serving not only as a source for the different HTML files but also for fetching malicious content and images used in designing the hijacked websites.

Underground Markets Activity

Through deep and dark web intelligence collection, we identified more than 51,000 compromised credentials originating from publicly circulating credential dumps and samples observed in the dark web. Analysis of these credentials shows a strong linkage to gambling-related infrastructure. The evidence indicates that credentials submitted into gambling platforms (or harvested from infected Android devices and hijacked sub-domains) were subsequently trafficked and monetized within underground cybercrime markets.

Massive Advertisement on Social Media and Other Popular Websites

When we finished mapping the extent of the threat actor’s infrastructure, we conducted additional open-source threat intelligence collection. We found an abundance of examples on Google search and social media platforms such as Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, Line, WhatsApp, and others.

The main purpose of these social media platforms is to advertise the gambling sites and generate traffic. Below you can see a screenshot from Facebook encouraging users to either visit a gambling website or download a malicious Android application.

This investigation has led us to identify many social media accounts associated with the activity. We believe these accounts allow the actors not only to increase the ratings of the different websites under their control but also to inject malicious content into those websites, as well as serve an important role in documenting the different exposed data.

We found on Docker Hub a couple of hundred container images related to this attack, mainly from 2022. These namespaces on Docker Hub didn’t contain any actual container images - they were empty. Instead, the attackers hid a link to gambling websites.

We also found a couple dozen users who shared numerous links related to the APT’s activity on the Scribd document-sharing platform, including gambling HTML templates, tutorials on how to bypass Indonesian government restrictions, and additional data related to promoting the gambling content.

Looking at different documents uploaded by those users, we found several interesting documents, including salaries, invoices, receipts related to web hosting and authentic government letters. The mentioned people in those documents appear to be legitimate Indonesian citizens, with some serving as IT workers in the country.

The Scribd accounts also contained multiple additional suspicious files, such as paychecks for Indonesian IT employees, as well as several letters sent to governmental entities in Indonesia, indications of a creation of a company, etc. This may also indicate that Scribd is used to upload or exfiltrate data from the APT’s victims.

Summary and APT Attribution

We gathered much information and raw data about the infrastructure and operation and analyzed it to better understand about the threat actor and possibly reach attribution.

We began by assessing the financial investment required to build and sustain an operation of this scale. In parallel, we traced the earliest observable components of the infrastructure and correlated them with evidence uncovered in our dataset. Extrapolating from these findings, the sheer breadth of this ecosystem, its blend of exploit-based techniques (WordPress and PHP vulnerabilities), opportunistic misconfigurations (dangling DNS and expired domains), underground marketplace presence, and the sizable financial resources necessary to maintain it, suggests a level of backing and operational maturity that surpasses typical financial cybercrime. Instead, the characteristics align more closely with those observed in state-sponsored threat operations.

Earliest appearance

We have a strong reason to speculate that this is an APAC based highly sophisticated Advanced Persistent Threat actor who has been active since at least 2011.

To find the earliest evidence in our database we outlined the domain eropabet[.]com which was linked to the APT’s infrastructure. This domain was first registered in 2011 and consequently renewed every year. Based on Whois records we speculate that it was held by a single entity since 2011. Below you can see the website as it appeared in the Wayback machines on June 8, 2012.

Evidence of Indonesian and Chinese Speaking Threat Actor

The APT who established and maintained the infrastructure is most likely to be Indonesian or has some Indonesian speaking operatives, since all the websites we witnessed targeted Indonesian speaking users, and most targeted sites were under the Indonesia TLD. The content itself is in Indonesian as the advertising operation.

Having said that, we also saw light evidence of Chinese speaking threat actor, when this string appeared in some html elements 创建监控项时,获得的"监控代码, translated as monitoring control and was found linked to API usage guide. Nevertheless, this is very circumstantial and weak evidence, which could be wrong.

Financial Strength

To evaluate the financial strength required by the APT we calculated the annual cost related to the vast domain infrastructure. We calculated the cost of domain registration, domain hosting, and certificates issue cost.

Thus, the minimum annual available resources the APT should possess is ~3/4 of million USD, the more realistic scenario it is 2-3 million USD; thus, the threat actor should have a solid financial capability in order to sustain this operation.

In this blog we depicted a vast infrastructure run by a sophisticated, well-funded, state-sponsored-level threat actor, below we suggest what are the possible goals of this attacker:

- Gambling is illegal in Indonesia; Thus, we assume this infrastructure might serve as an underground organization promoting gambling in the country. The scope of infrastructure is probably to enable scale and velocity and make it difficult for law authorities to take it down.

- This infrastructure has a gambling front mask to conceal that it is used by threat actors for C2 and anonymity services, like a Chinese ORB network.

- It could serve for two purposes by two entities. One is a true in-nature gambling infrastructure and the second is an affiliate entity that promotes the gambling infrastructure (redirect users to the gambling infrastructure). It can explain why there are so many domains and hijacked subdomains that redirect to the gambling sites and don’t host the gambling themselves.

Mapping the infrastructure to the MITRE ATT&CK framework

In this section we offer a map for the components used by the APT, as they are described above in the text, to the corresponding techniques of the MITRE ATT&CK framework:

MITRE ATT&CK mapping

Recon/Resource Development

- Acquire/Compromise Infrastructure (T1583 / T1584): mass domain registrations, subdomain takeovers.

- Stage Capabilities (T1608): hosting templates/APKs on public platforms.

Initial Access

- Exploit Public-Facing Application (T1190): WordPress/PHP compromises.

- Valid Accounts (T1078): use of stolen tokens/credentials.

Execution/Persistence/Privilege

- Server Software Component: Web Shell (T1505.003): on hijacked sites (indicators present in repos).

Credential Access / Collection

- Steal Web Session Cookie (T1539): via domain-scoped cookie capture on hijacked subdomains.

Command & Control

- Application Layer Protocol (Web) (T1071.001) & Encrypted Channel (T1573): HTTPS C2.

- Proxy/Domain Fronting-like Cover (T1090): NGINX reverse proxies on reputable FQDNs.

Impact

- Exfiltration Over Web Services (T1567): telemetry to shared endpoints (e.g., namesvr).

Detecting Malicious Infrastructure and Mitigation Steps

Even in today’s cybersecurity landscape, where AI-enabled adversaries build attack infrastructure in minutes, this is an impressive and long-built operation. Malanta approach is focused around preventing breaches before they happen by surfacing Indicators of Pre-Attack (IoPAs) such as newly registered brand-mimicking domains, cloud-hosted command-and-control beacons, and AI-generated phishing kits still in staging.

As part of our commitment to strengthen and protect the broader community, we published in our GitHub repository the full list of domains registered and operated by this APT as part of its long-standing infrastructure. However, because many hijacked subdomains still pose an active and serious risk to thousands of businesses and individuals, we cannot publicly release the subdomain list.

If you wish to verify whether any of your domains or subdomains appear in the attacker’s infrastructure, we strongly encourage you to contact us at the email below. We will assist you in assessing exposure safely and privately.

Below are some guidelines that can help you detect and remediate malicious IoPAs and IoCs.

For domain owners / website teams:

Eliminate takeover risk

- Audit DNS for dangling CNAMEs/A records to cloud resources (Azure, GitHub Pages, Amazon S3/CloudFront, etc.).

- Enforce short TTLs and automated decommission cleanup for cloud origins.

Harden cookies & origin policy

- Prefer host-only cookies (omit the Domain attribute) for sensitive apps; set HttpOnly, Secure, and appropriate SameSite.

- Implement CSP and Subresource Integrity where feasible.

Continuous monitoring

- Alert on new subdomains resolving to cloud-vendor spaces you don’t own.

- Watch for unexpected TLS certificate issuance for your eTLD+1.

For defenders / SOC:

Network analytics

- Flag outbound traffic where SNI/Host matches government or enterprise FQDNs unrelated to your org, but the destination IP/ASN is cloud commodity space not historically seen.

- Hunt for unusual POSTs to paths/templates associated with Lazada/eBay lookalikes from corporate hosts.

Endpoint & web logs

- Block/alert on beacons to jp-api.namesvr[.]dev and newly observed domains with gambling keywords contacting S3.

- Detect browsers visiting your brand’s hijacked subdomains immediately preceding privilege escalation or sensitive actions.

Mobile controls

- Restrict installation from unknown sources; enforce Play Protect/MDM policy.

- Apply DLP to external-storage reads/writes by unapproved apps.

Rapid remediation playbook:

- Take back hijacked subdomains (fix DNS, reclaim cloud resources, revoke certificates).

- Invalidate sessions for affected users; rotate tokens/credentials found in leaks.

- Purge CDN caches and remove injected SEO links/backdoors.

- Blocklist observables (see below) and monitor for re-appearance (actor rapidly reseeds).